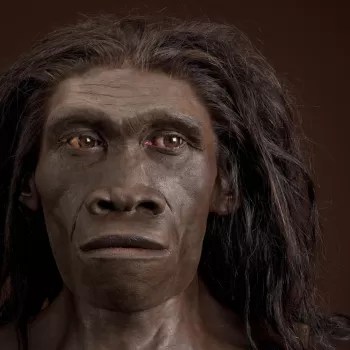

Over the last few weeks we have seen how humans and Neanderthals each lived in the Near East, how each was present in different areas, or in the same area at different times. This week humans move once again out of Africa and northwards across the Near East. Unlike in the Middle Palaeolithic, this time humans are here to stay and it will be the Neanderthals who eventually cease to be found in the Near East after about 40,000 years ago.

The first indication that we have of the change into the Upper Palaeolithic comes from changes in the stone tools. As we know, the Middle Palaeolithic relied heavily on the use of the Levallois technique and the flakes or modified flake tools which were made using this method. Other types stone tools were around in the Middle Palaeolithic, but were found as more minor parts of the stone tools recovered from Middle Palaeolithic sites. One of these was blades, which are found in the Middle Palaeolithic but are only a small portion of the stone tools made.

This changes in the Upper Palaeolithic, where the stone tool technology is dominated by blades and blade tools. However, in the early stages of the Upper Palaeolithic – the transition from the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic, sometimes called the earliest Upper Palaeolithic or the Initial Upper Palaeolithic, from about 49,000 to 40,000 years ago – we find Levallois flakes and other Mousterian tool types present as the minor component alongside this majority of blades. In other words, the Middle Palaeolithic distribution of stone tools has turned backwards, with the formerly minor part now being dominant, and also the reverse.

There are two ways of looking at the change from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic. One is the arrival of a new and unrelated way to doing things – making tools, hunting, gathering plants, etc. – from somewhere outside of either the Near East as a whole or outside of a particular region of the Near East. The other way of looking at this change is the local development of technology which sees major changes but ones which are evolving out of local traditions. Each of these has been argued to be the case in different areas of the Near East, with the introduction of an already-formed new tool technology in some parts of the Caucasus and the Zagros, and the development of new methods based on local traditions in the Levant and also in the Zagros.

It is likely that both of these visions of the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition are correct, and that the change from one Palaeolithic to the other – and the change from Neanderthals to humans – may have been different depending on where in the Near East you were. In the Levant, new discoveries suggest that humans and Neanderthals lived in this same region (or at least in the southern parts) for several thousand years. Humans may even have arrived here a few thousand years before we see changes in the stone tools and other technology which we recognize as the beginnings of the Upper Palaeolithic.

Episode Bibliography:

Brzilai, O. and Gubenko, N. 2018. Rethinking Emireh Cave: the lithic technologyperspectives. Quaternary International 464: 92-105.

Becerra-Valdiva, L., Douka, K., Comeskey, D., Bazgir, B., Conard, N.J., Marean, C.W., Ollé, A., Otte, M., Tumung, L., Zeidi, M. and Higham, T.F.G. 2017. Chronometric investigations of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in the Zagros Mountains using AMS radiocarbon dating and Bayesian age modelling. Journal of Human Evolution 109: 57-69.

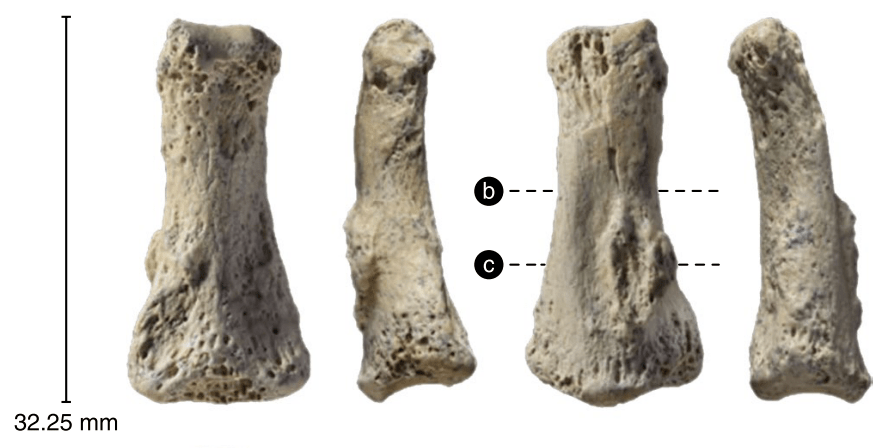

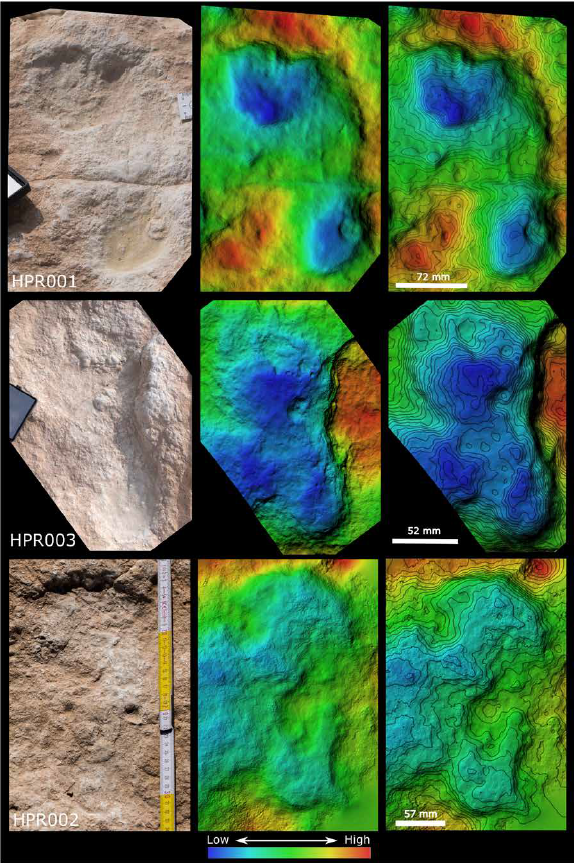

Borgel, S., Latimer, B., McDermott, Y., Sarig, R., Pokhojaev, A., Abulafia, T., Goder-Goldberger, M., Barzilai, O. and May, H. 2019. Early Upper Paleolithic human foot bones from Manot Cave, Israel. Journal of Human Evolution doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102668

Friesem, D.E., Malinsky-Buller, A., Ekshtain, R., Gur-Arieh, S., Vaks, A., Mercier, N., Richard, M., Guérin, G., Vlladas, H., Auger, F. and Hovers, E. 2019. New data from Shovakh Cave and its implications for reconstructing Middle Palaeolithic settlement patterns in the Amud drainage, Israel. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology 2: 298-337.

Gasparyan, B. and Arimura, M. 2014. Stone Age of Armenia: A Guide-Book to the Stone Age Archaeology in the Republic of Armenia. Kanazawa: Center for Cultural Resource Studies, Kanazawa University.

Ghasidian, E. 2013. The Early Upper Paleolithic Occupation at Ghār-e Boof Cave. A Reconstruction of the Cultural Tradition in the Southern Zagros Mountains of Iran. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag.

Ghasidian, E., Heydari-Guran, S. and Lahr, M.M. 2019. Upper Paleolithic cultural diversity in the Iranian Zagros mountains and the expansion of modern humans into Eurasia. Journal of Human Evolution 132: 101-118.

Goder-Goldberger, M., Crouvi, O., Caracuta, V., Horwitz, L.K., Neumann, F.H., Porat, N., Scot, L., Shavit, R., Jacoby-Glass, Y., Zilberman, T. and Boaretto, E. 2020. The Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in the southern Levant: new insights from the late Middle Paleolithic site of Far’ah II, Israel. Quaternary Science Reviews 237: 106304.

Golovanova, L.V. and Doronichev, V.B. 2012. The Early Upper Paleolithic of the Caucasus in the west Eurasian context. In M. Otte, S. Shidrang and D. Flas (eds.), L’Aurignacian de la grotte Tafteh etson context (fouilles 2005-2008). Liège: ERAUL: 137-160.

Goring-Morris, N. and Belfer-Cohen, A. (editors). 2003. More than Meets the Eye: Studies on Upper Paleolithic Diversity in the Near East. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Goring-Morris, N. and Belfer-Cohen, A. 2020. Noisy beginnings: the Initial Upper Paleolithic in Southwest Asia. Quaternary International 551: 40-46.

Greenbaum, G., Was inter-population connectivity of Neanderthals and modern humans the driver of the Upper Paleolithic transition rather than its product? Quaternary Science Reviews 217: 316-329.

Hershkovitz, I., Marder, O., Ayalon, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Yasur, G., Boaretto, E., Caracuta, V., Alex, B., Frumkin, A., Goder-Goldberger, M., Gunz, P., Holloway, R.L., Latimer, B., Lavi, R., Matthews, A., Slon, V., Bar-Yosef Mayer, D., Berna, D., Bar-Oz, G., Yeshurun, R., May, H., Hans, M.G., Weber, G.W. and Barzilai, O. 2015. Levantine cranium from Manot Cave (Israel) foreshadows the first European modern humans. Nature 520: 216-219.

Kadowaki, S., Tamura, T., Sano, K., Kurozumi, T., Maher, L.A., Wakano, J.Y., Omori, T., Kida, R., Hirose, M., Massadeh, S. and Henry, D.O. 2019. Lithic technology, chronology, and marine shells from Wadi Aghar, southern Jordan, and Initial Upper Paleolithic behaviours in the southern inland Levant. Journal of Human Evolution 135: 102-646.

Kuhn, S.L. 2004. From Initial Upper Paleolithicto Ahmarian at Üçağizli Cave, Turkey. Anthropologie 42(3): 249-262.

Nasab, H.V., Berillon, G., Jamet, G., Hashemi, M., Jayez, M., Khaksat, S., Anvari, Z., Guérin, G., Heydari, M., Kharazian, M.A., Puaud, S., Bonilauri, S., Zeitout, V., Sévêque, N., Khatooni, J.D. and Khaneghah, A.A. 2019. The open-air Paleolithic site of Mirak, northern edge of the Iranian Central Desert (Semnan, Iran): evidence of repeated human occupations during the Late Pleistocene. Comptes Rendus Palevol 18: 465-478.

Nishiaki, Y. and Akazawa, T. (editors). 2018. The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archaeology of the Levant and Beyond. London: Springer.

Pearson, O.M., Pablos, A., Rak, Y. and Hovers, E. 2020. A partial Neandertal foot from the Late Middle Paleolithic of Amud Cave, Israel. PaleoAnthropology 144: 98-125.

Pinhasi, R. Gasparian, B., Wilkinson, K., Bailey, R., Bar-Oz, G., Bruch, A., Cataigner, C., Hoffman, D., Hovsepyan, R., Nahapetyan, S., Pike, A.W.G., Schreve, D. and Stephens, M. 2008. Hovk 1and the Middle and Upper Paleolithic of Armenia: a preliminary framework. Journal of Human Evolution55: 803-816.

Sarig, R., Fornai, C., Pokhojaev, A., May, H, Hans, M., Latimer, B., Barzilai, O., Quam, R. and Weber, G.W. 2019. The dental remains from the Early Upper Paleolithic of Manot Cave, Israel. Journal of Human Evolution doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102648

Stiner, M.C., Munro, N.D. and Surovell, T.A. 2000. The tortoise and the hare: small-game use, the broad-spectrum revolution and Paleolithic demography. Current Anthroplogy 41(1): 39-73.

Tsanova, T. 2013. The beginning of the Upper Paleolithic in the Iranian Zagros. A taphonomic approach and techno-economic comparison of Early Bardostian assemblages from Warwasi and Yafteh (Iran). Journal of Human Evolution 65: 39-64.